The Rise of the Long-Term Contract and What it Means for the Future of the MLB

Red Sox third baseman Rafael Devers was the latest in a string of players to sign long-term deals this offseason when he signed an 11-year, $331 million contract. Via Boston.com

Rafael Devers. Aaron Judge. Mookie Betts. Francisco Lindor. Fernando Tatis, Jr. Bryce Harper.

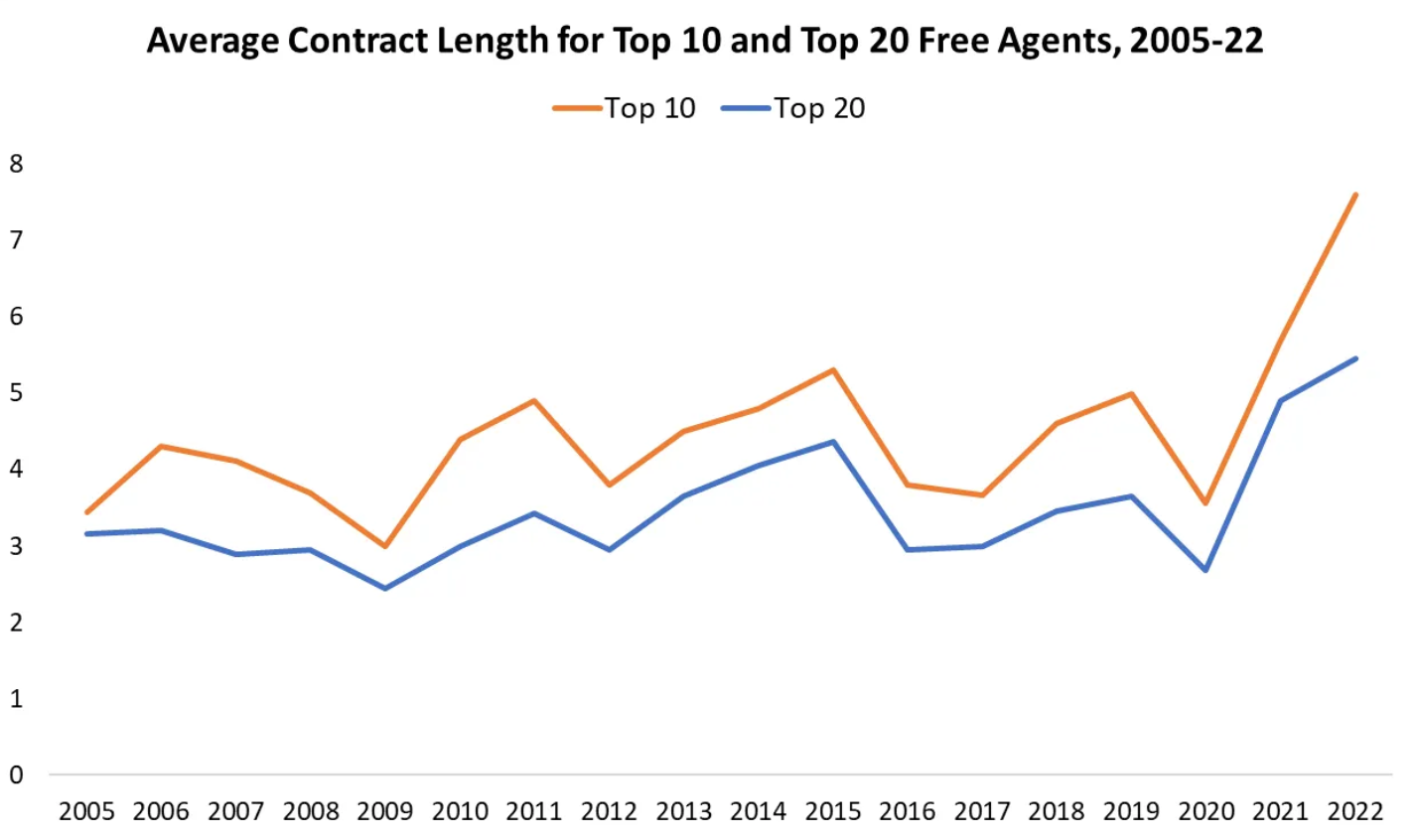

What do these players and so many others have in common? Over the past few years, each of them has agreed to a contract in which they will be paid for nine years or more. Do the owners and general managers of these players’ teams expect all of them to play into their age 40 seasons? While it’s possible, the answer is…probably not. This recent trend has made headlines for the past few offseasons, and it’s clear that especially the upper echelon of players is getting locked up for what, at least in the world of baseball, feels like an eternity. The graph below shows a concerning spike over the past few years in the length of these contracts.

Graph courtesy of The Ringer, an SBNation affiliate

If the teams paying these players don’t anticipate them fully finishing out their contracts, then why sign them? The answer lies in the competitive balance tax. The MLB is notorious for not having a hard salary cap, unlike many other major sports leagues. Instead, they have a system called the competitive balance tax, more commonly known as the luxury tax. The system works by adding together each player’s contract’s average annual value, or “AAV”. When team payrolls go above the luxury tax threshold, which sits at $233 million for the upcoming season, they incur a percentage tax on those dollars. The first year the team is over the threshold, those overages are taxed 20%, then 30% in the second consecutive year, and any years after that are taxed 50%. Seems like a hefty price to pay for wins.

Enter Steve Cohen, the hedge fund manager-turned-majority owner of the New York Mets, who took over in October 2020. With a net worth of $15 billion, Cohen hasn’t held back, especially this offseason, and that attitude has led to a projected 2023 payroll of close to $300 million for his team, the highest in MLB history.

This skyrocketing payroll is further adding to the complaints of fans that state that baseball “just isn’t fair”. As long as big-market teams like the Mets can pay their players handsomely and still be profitable, they’ll have a massive advantage over teams like the Athletics, who have a projected payroll this upcoming season of around $25 million.

The luxury tax we have today, which went into effect in 2002, was aimed at targeting this exact problem. But the recent rise of long-term deals as shown in the graph above is directly counteracting its intent. With these deals, a player like Rafael Devers of the Red Sox can still be paid $331 million, but spread over 11 years. Instead of, say, a five-year deal, where Devers would count for $66 million toward the luxury tax threshold, his new deal brings that number down to around $30 million annually, giving his general manager much more room under that threshold to work with.

This new trend seems to be the exact opposite of the intent of the CBT. The MLB’s Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) states that neither players nor clubs shall enter into any agreement “designed to defeat or circumvent the intention” of the luxury tax. While the language regarding the tax is subject to interpretation, there’s no doubt that the MLB will eventually draw the line and step in.

But what can the league do?

Ken Rosenthal said it best in a 2022 article for The Athletic:

“And if the league acted, it would face a fight. The Players Association almost certainly would file a grievance if MLB disapproved a deal on the basis of its length, according to a source with knowledge of the union’s thinking. The players also would object if the league sought to limit the lengths of contracts in bargaining, viewing it as a restriction on the market.”

There’s no question that front offices have plenty of motivation to keep increasing contract lengths, lowering AAVs and spreading out payments. With the disparity between the big-market franchises and small-market ones already such a defining trait of the league, it won’t be long before the MLB decides that a team has offered a contract that crosses the line, and shuts it down. If and when that happens, things could get nasty. MLB fans should brace themselves for a fight with big-market and small-market teams pitted against each other, with heavy implications at stake.